As we approach the late summer and early fall, the clinical signs of West Nile Virus (WNV) will peak in number. Governments, private citizens and animal owners have all quickly taken steps to manage the threat of the disease since North America's first reported case in New York City in 1999. However, since then, concerns over the disease have taken on mythical proportions. Experts predict that the number of cases of WNV will peak in mid August.

Preventing West Nile Virus.

Wetter-than-normal conditions combined with warmer weather have experts worrying about an increase in mosquito populations, which could trigger more cases of West Nile virus in people and pets this year.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Climatic Data Center (Libertyville, 111.), above-average precipitation and temperatures across the United States made the start of 2005 one of the wettest and warmest in history.

Even a small bucket that contains standing water for only four days can become home to many mosquitoes, according to Pennsylvania's Department of Environmental Protection (Harrisburg). Here are some tips for eliminating standing water around homes:

+ Dispose of tin cans, plastic containers, ceramic pots or similar water-holding containers on your property. Do not overlook containers overgrown with aquatic vegetation. Pay special attention to discarded tires.

+ Drill holes in the bottom of outdoor recycling containers. With holes on the sides, enough water can collect for mosquitoes to breed.

+ Clean roof gutters on an annual basis. Easily overlooked, roof gutters can produce millions of mosquitoes each season.

+ Turn over plastic wading pools when not in use.

+ Turn over wheelbarrows, and do not allow water to stagnate in birdbaths for more than four days.

+ Aerate ornamental pools or stock them with fish. Water gardens become major mosquito producers if they stagnate.

+ Clean and chlorinate swimming pools that are not being used. Mosquitoes may breed in water that collects on swimming pool covers.

+ Use landscaping to eliminate standing water. Mosquitoes will develop in any puddle that lasts for more than four days.

The disease was first discovered in a woman in the West Nile district of Uganda in 1937. An outbreak in Israel in 1957 was when the virus was first recognized as a cause of severe encephalitis in man. The disease soon migrated into Egypt and France where it was diagnosed in the equine population in the early 1960s. Since then, it has been detected in birds, humans and horses in Africa, Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

It is well known that WNV is deadly to the horse and some wild bird population. But, what of our cats, dogs and pet birds?

For at least some individuals of some species infected under lab conditions (a Budgerigar, a Monk Parakeet, and two Japanese Quail), viremias did not develop at all, viral particles were not detected in blood taken subsequently. Other species infected under lab conditions developed detectable viremias, but their immune systems produced antibodies that then beat back the virus; virus particles disappeared from the blood as antibodies increased (e.g., Mallards, American Kestrels, Mourning Doves, Rock Doves -pigeons, American Robins, and Red-winged Blackbirds). The timing of this battle differs for different species, but the period when virus particles can be detected in blood is generally 0-8 days after infection; antibodies are generally detectable after 6-7 days (Dr. Nick Komar, Arboviral specialist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). It is not yet known for how long "immunity" lasts in different species, nor whether or not individuals surviving infection go on to live "normal" lives.

According to Dr. Grant Maxie, Manager of the Animal Health Laboratory at the University of Guelph, "Yes, West Nile virus can infect dogs and cats, but they rarely appear to develop disease."

Research indicates that dogs and cats are capable of becoming infected with the virus that causes West Nile, but evidence so far shows that for the most part, they simply don't show signs of the clinical disease. A survey conducted by 15 veterinary clinics in Louisiana between August 25 and November 2 last year tested 442 dogs and 138 cats for West Nile Virus. Of those, 9.4% of cats showed a seroprevalence with 26.2% of dogs testing positive. The incidence of positive cases was twice as high in strays than family dogs, and 19 times higher in outdoor vs. indoor dogs. No deaths were noted.

Because this disease is so new to North America, the medical community continues to make new discoveries relative to WNV. However, the Centers for Disease Control in the U.S. indicates that in addition to birds (138 species infected), horses and humans, WNV has been known to infect camels, cattle, sheep, mountain goats, cats, bats, chipmunks, skunks, squirrels, domestic rabbits, and dogs. The puzzling aspect with these species, however is that aside from horses, wild birds, and a fraction of the humans affected by WNV, it does not appear to cause extensive illness.

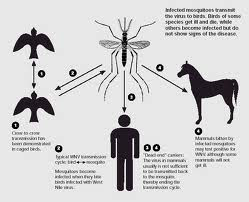

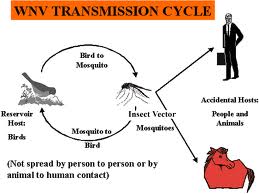

West Nile virus falls into a category of viruses called flavivirus, a member of a larger group of viruses called arboviruses, which are transmitted by blood-sucking vectors such as mosquitoes. Using birds as the host, they become a transmitter by biting the infected bird (or other species), incubating the virus for 5 to 15 days, and then transmitting the virus to other birds, humans or animals. Horses have had access to a vaccine for West Nile virus for the past two seasons. No vaccine for humans is presently available, and researchers find it difficult to predict when a vaccine may eventually come to market..........

Is the vaccine available in Illinois?

Fort Dodge Laboratories received a conditional license for a killed virus product on August 1, 2001. Conditional licensing means that the product has been shown to be safe, pure, and have a reasonable expectation of efficacy in preventing illness. On August 7, IDOA approved the sale of this vaccine to licensed veterinarians in Illinois. The vaccine can only be administered by a veterinarian. Fort Dodge recommends administering two 1 milliliter intramuscular doses, three to six weeks apart, followed by an annual booster.

An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure...

There are countless resources available with recommendations on protecting ourselves from potentially infecting mosquitoes. Probably the easiest one is to apply an insect repellent containing DEET. However, it is critical that pet owners not apply human products to pets.

Too many pets have suffered serious side effects by Ingesting human-labelled products applied by well-meaning pet owners. If you're going to the cottage, or a location where you're really concerned about a high mosquito population, bring along products such as pyrethrin-based insect repellents specifically designed, tested and labeled for safe use on companion animals. Owners must also recognize that mosquitoes are most active between dusk and dawn, and keep pets indoors during these periods.

Pet owners must also weigh the risk of their pet contracting WNV versus against the potential long-term effects of using insect repellents. It is up to the owner, to assess their level of risk aversion.

Perception Does Not Necessarily Equal Risk...

Although the media continues to bombard the public with messages about West Nile Virus, the risk needs to be properly quantified:

1. It is estimated that less than l% of mosquitoes in regions affected by WNV actually carry the virus,

2. The vast majority (nearly 99%) of people who are infected don't feel any symptoms at all.

3. Unless the disease progresses to cause encephalitis, it's usually over in less than a week. (Severe illness, including encephalitis usually occurs in the very young, elderly or those with weakened immune systems. Of those who develop encephalitis, the mortality rate is estimated to be between 3-15%).

What is extremely necessary is for veterinarians and pet owners to properly assess the actual risk of WNV to themselves and their pets. The Centers for Disease Control in the U.S. reported only one death in an 8-year-old dog, which happened to be concurrently immunocompromised, in the Chicago area last year.(2002)

A Symptom of What?

Ultimately, if there is still concern that a pet has WNV, there are certain clinical signs that may indicate disease, including incoordination, depression, decreased appetite, difficulty walking, tremors, abnormal head posture, circling and convulsions. However, these signs may indicate other very serious neurological conditions, and a thorough veterinary examination is the only means of ensuring an accurate diagnosis.

Confirmation of a WNV diagnosis is usually accomplished with a blood test (VecTest capture ELISA and PCR) or post-mortem examination. WNV is an immediately notifiable disease under the Health of Animals Act, which means that all laboratories are required to contact the USDA Food Inspection Agency upon suspicion or diagnosis of the disease. District veterinarians of the USDA are also excellent local sources of information on WNV.

Fundamentally, veterinarians should take reasonable precautions to prevent West Nile virus infection in themselves, their pets, and patients. It's important that pets and people enjoy the season, mosquitoes and all.

|